[In a blatant act of e-vandalism, I have retroactively renamed Baz’s November posting ‘Earthrise Repair Shop’ and cut everything in that posting except for Phil Smith‘s reflections below. This is because the entirety of Baz’s post has now been moved to its rightful place as a ‘Project’ page on the main menu of this site… But I’ve left Phil’s thoughts here because — besides responding directly to Baz’s ERS meadow meander (and they still also sit in their correct place in his collage of response on the ERS page) — they also link directly on from his earlier blog posting “Footnotes on Apocalypse”… and relate also to our discussions with the Environment Agency (“Welcome to Eastville”). So I’ve left them here to preserve and emphasise that blog continuity…. Although Baz’s redactions of certain pieces of descriptive information – XXXXX – also remain intact. SB]

Theses nailed to the cottage door

1/ Pondering what a performance reflecting on environmental change might be, it became difficult not to abandon the [walking] task in order to reflect on environmental change, as if the latter were necessary for the former. This may be a trap.

2/ That reflections are less distinct in experimental science than in popular science publishing, let alone those narratives of environmental change that surface in both ‘serious’ and clownish or abject mass media.

2/ For dramaturgical rather than empirical reasons, it is hard to believe (feel entertained or intellectually satisfied by) the narrative of the Good Earth (sub-plot: wicked humans). Even the most heartfelt and well-researched accounts of “pollution” read too much like laws of ritual purity. A spiritual or ideal cleanliness is an organic death.

2a/ Is there a kind of doubleness in the theatre of “green”? – that the Earth is good but that we should fear its anger at what we do; that the Earth will wipe-us-out. So the Earth is called “good”, but described as though it is what is otherwise called “evil” – a terrain of voiceless, unreflexive danger?

3/ If human consciousness is part of Nature, and technology, its objects and intentions, are parts of Nature (so much so that the word “part” becomes suspicious – as if it might have the same relation to Nature as a partial object to an individuation), suspension bridges and the skeletal structures of large plant-eating dinosaurs are made to the same pattern, are responses to the same physical forces. “The mathematics are out there” (Roger Penrose).

4/ It is (memetically) tempting to believe that ideas and images prosper and propagate in ways not dissimilar to biological information.

5/ Any ‘reflection’ will take place on a contorted and contorting “surface”, or rather on a series of contorting reflective surfaces weaving in and around each other while moving also in relation to the motions of changes in/being the environment.

6/ Empirical science is telling us that it is between very probable and a cast iron certainty that human actions have triggered an ongoing and accelerating warming of the planet, and that we cannot be certain what the consequences will be, but that we would be foolish to assume that the changes will be comfortable (or even life-sustaining) for much organic life on Earth.

6/ But…

6/ Apocalypse is a socially attractive fiction: like utopia it implies a bounded space (rather than city wall or island shores, apocalypse is bounded by isolation and the eradication of complexity). It allows everyone to play – if the game is feral survival – to drop the usual rules, it brings the cancellation of all rents, debts, appointments. A vicious holiday. The illusion of starting from scratch (following Jesus, Thoreau and Breton – abandoning communality to take a walk.) Despite these qualities, the narrative of apocalypse has become an assumed part of popular reflecting on environmental change. It is the something that the “we” (when this fiction of an aggregation of individual consumers forms an audience, assembled in the absence of “good taste”) secretly or not so secretly want: not surprisingly, as the narrative is constructed for the “we” to want it (and has survived by appearing to be constructed for, even by, us). It is the contemporary sublime, this time written by the landscape gazing mutely back.

6/ In Global Catastrophes, the vulcanologist Bill McGuire’s most credible narratives for a Sixth Mass Extinction are all “natural”. Human behaviour, more than it “damages” a planet separate from itself, makes itself vulnerable to a recidivist planet that has repeatedly generated “catastrophes”. And what if the planet “wants” this? In the same way that an aggregated and rough audience “wants” apocalypse? Does the planetus (the planet including us) have a memetics?

6/ We are now a geological force.

6/ A child sneaked in at the back of a recent screening of The Cove and watched with care as the nets of the fishermen herded the dolphins towards the thickening shallows; she saw the delegates from landlocked and impoverished nations smiling, she saw Sea Worlds that reminded her of the refugee camps, she saw the educational murals, she saw the tins of chemical tuna in the coolers, and she remembered the old old story that they were always making up in the camps and playgrounds; about how the instructions for people and machines are not written by good people choosing good things, but how they come from a spectre that no one ever quite sees, who is everyone and who no one is like, who no one has chosen and who commands almost complete consent and who hurts everyone even though it owes everything to them, and that it is this very debt that determines everything everyone does, from the direction of the cars to the colour for stop and the colour for go, and that no one who walks on two feet and wears a hat, a belt or a kimono can escape it. Running from the cinema, the child out-stripped the angry charity worker, pausing at the traffic island, hauling on the fumes and the smell of street food. She ran her own movie, an anime, of the flow of the cars that was the flow of the XXXXX, and of the cruelty of the fishermen’s knives that was the strike of a fish’s jaws; and everything that her human character did was seized on by artists and transformed; highways into the trails of slugs, plans into deserts, blueprints into reflections on the surface of a pond, and wounds into new organs.

6/ That if we want to understand (not sentimentalise) an ecology we need the (strictly limited) paranoia that we can accrue by first assuming that we are in a food chain with it (it-is-out-to-get-us), wary of revenging “Gaia”, defensive against the anger of “Mother Earth”… look at the building/s around you, and now replay Marx’s parable of the architect and the bee – does it still make sense? Look at the buildings again. Now walk the story, the buildings, the architects and the bees into the XXXXXXXXXXXX. (The task of advocating flood defences, and the quality of that advocacy, might be more important and more significant than it seemed at the time.)

6/ “Never set foot in a fallout shelter”, Mutant advised in the 1960s, for “it is better to die standing with all the cultural heritage of humanity, the perpetual modification of which must remain our task.” “Nuclear weaponry’s main function is to deter not the enemy but the state’s own population. Contrary to the Ban the Bomb movement, this position sees not nuclear annihilation as the main threat, but the disarming of critique… One wonders how much the twenty-first century’s obsessions with things environmental might likewise play a demobilizing role.” (McKenzie Wark, The Beach Beneath The Street) Over and above the author’s political opinions here, what if stories are inadequate (asks the storyteller)? What if the storytellers are inadequate (asks the stories)? What if the vocabulary has been grinding the words down to letters again (vdesc w2.%st sdv^7=sst b3s)?

The invitation

After Steve had kindly posted on the blog some notes of mine under the heading “Footnotes for Apocalypse”, I received an email from Baz, inviting me to visit him at his cottage. I can’t recall the exact wording, but he wanted me to see a meeting point of what passes for heaven and hell in the contemporary world that had opened up on his land. I hope I do not misrepresent him when I say that his reasons for inviting me were partly practical (to test the opening – I think 5 people had previously tried it out), partly his partial identification with something in the “despair” of the Footnotes, and partly a pastoral care for my own wellbeing. These partlies all took on the qualities of partial objects – voices without bodies, shapes without substance, maps without mass. All of which were to coalesce in the complex, but organic and topological opening, a kind of intestine, which I now have as a part of my body and out of my control. Baz said nothing more by way of explaining the heaven/hell site. We arranged a date and then brought it forward ten days: the “meadow” had abruptly come to a good moment for me to visit. I caught the train a day later. An hour having passed along the flat valley floor, and I was met by Baz at the station and was at the meadow shortly after that.

The meadow and the matrix

Baz’s cottage sits at the meeting point of two valleys, each with its own stream. The streams meet close to the road, a former drovers’ route from XXXXXXXXXXX to XXXXXXXXXXX, and one runs alongside it. Adjacent to the cottage are areas of garden, a pond, a fenced area for chickens and a large meadow, divided in various ways, and a small strip of woodland in which a tiny quarry is shaded. The land is overlooked and protected on one side by a wall of large, mature conifers that are due for felling: a kind of threat, at present mitigated by a [neighbour’s] private inertia. An occasional vehicle passes by on the old drovers’ route.

The heaven/hell confluence is a figuring of XXXXXXXXX “mapped” onto (trodden into) the meadow. I walk this “maze” for a while guessing what it might be (first guess: fish) and then Baz lets me in on it.

I walk it some more, climb up a long ladder leaned against a tree growing from the edge of the tiny quarry to photograph the XXXXXXXXX chart from above. Although it is on a slope the outline cannot be seen clearly from anywhere on the rising ground. We go inside for a cup of coffee. Talk about what it is, this meadow chart, how it might be used. About apocalypse and its narratives and the role of cottages in them. A woodpecker feeds on the bird table. Then we come outside once more and I walk and run the XXXXXXX for, say, 12 or so circuits. I have very little idea how long it takes – 5 minutes? An hour? The gut stretches. Pushing things around in peristaltic waves.

XXXXXX and buzzard

I began by walking the XXXXXXXXXXX at an even, brisk pace. Very quickly I was able to look around and began to notice rather large features that I had previously ignored: I was amazed to notice that there were power-lines hung across the meadow on tall poles. Through trees I glimpsed a building on a far horizon… it rained, the sun shone, the butterflies (meadow brown and cabbage white) retreated and reappeared according to the light, I trampled the grass that had been trampled, I followed the lie of the stalks as Baz suggested; what had seemed enigmatic became a simple spectral XXXXXXXXX down which I floated.

Only when I attempted to follow the circling of a buzzard while walking very slowly did I become giddy and stumbled.

At one point, in response to the dip of the ground, my skeletal frame crunched, then realigned itself into a more “satz”-like state of preparedness.

I wondered why neither Baz nor I had mentioned to each other the XXXXXXX that stretched across the middle of the “map”, a kind of XXXXXXXX, necessitating a step or leap when moving from one XXXXXXXX to another. I think now of the initiations of young XXXXXXXXX and the impersonation of the XXXXXX.

At times the path began to disappear and the meadow became a woozy mass of appearance, through which muscle memory guided me precisely. Whether by pigment or scintillation, the tops of the grasses appeared misty.

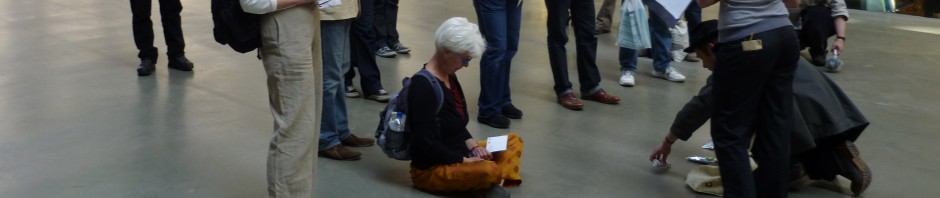

A couple of times I saw Baz moving about near the gorse. (Later we would talk about ordeal, and setting other walkers the task of walking the XXXXXXXX through the gorse and the bramble.) Then I saw him at the top of the precarious ladder. Another hawk. “Do you mind if I document the documenter?”

We were going round in XXXXXX.

And now that I am away from the XXXXXXXXX and trying to write about them, there is a swirl of desperation. I sit and stop, but the stiller I get, the tighter the vortex becomes. It has a life of its own, this desperation – a ghost sheriff emerging from the history of small company towns, a fleet of possessed tanks rolling down the streets of wooden shacks, a matrix of barbed wire pulling the countryside tighter and tighter – its personifications are utterly unhelpful, truly and unusually without meaning or allusion: the more I sit here the more they pass uselessly by on those looping XXXXXXXXXX. An accursed share. Refreshing the memory; unfathomable, mute.

Two days before my walk in the maze, I had stood on the very point of Dawlish Warren, a long spit of sand dune, where the plastic containers and fish skeletons are bleached white by sun and salt. Talking with a sculptor about her trodden path made in a wood near Darmstadt, walked and scuffed into the shape of a wolf, at the cost of a pair of boots – http://2010.waldkunst.com/kuenstler/caroline-saunders – and it had been all about meanings in the rip and pull and counter-current, the forces of the river meeting the forces of the incoming tide, forming the kinds of uzumaki that transform communities in a few moments. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uzumaki

How complacent that seems now.

Provisional Findings

The maze pushes the focus outwards. It allows little introspection.

The maze slopes and constantly challenges the body to shift its centre of gravity in response. The maze is somatic.

The maze “empties” the mind – by shaking the brain it opens up coagulated gaps, rendering them vulnerable to an outside that rushes in to fill the tiny sucking vacuums.

The maze strips and rips the shape from the experience, hurls meanings to the beside, by the centripetal force of the whirl of the meadow-XXXXXXXX, by its performance-likeness, by its flat globalisation of a place with the footprint of a large cottage, its conceptualisation and its projection; these XXXXXXX, unlike the deadly (to human and dunes) ones at the Warren, refuse to be employed for anything, avoid signing up to convictions, are on no payroll, do no work and are not rebellious. They plough on without decision, enigmatic – as if behind a faceless face things are gathering towards a spasm that never comes. Relax. Don’t do it.

I am not very affected by this. Except for this prosthesis that I have now got attached to me. Thrashing about.

On the way to lunch at the nearest village pub we pass through an enormous market square and by a huge parish church: Baz’s cottage sits within a nexus of routes and staging posts that have been of great commercial, transportational and religious importance. Baz’s XXXXXXXXXX meadow-maze connects to the flows of this greater (if now creaky) machine, slipping its gears, uncomfortable, revving its frame in surges of energy that fail to grip onto the shafts, whirring as if it might throw something off, suddenly, unplanned.

“What’s the worst thing that can happen here?”

Baz describes rising sea levels that might bring the water close by, but not as far as the cottage.

Cottages (and farmhouses) are sites for apocalypse narratives: 28 Weeks Later, Night of The Living Dead, The Happening, Dead Snow, Weekend, War of the Worlds, Tripods … they are foolish retreats to the domestic and the (slightly) extended or reconstructed family. They quickly become places of siege and once this happens the narrative generally runs out of steam – most sustained apocalyptic narratives are those in which new kinds of communities are established (The Changes with its neo-village including processional Sikh metalworkers, The Stand with its proto-societies of good and evil, The Walking Dead with its shifting mobile community détourning prisons). The Road is an interesting exception – its journey and its text barely pause long enough for anywhere to matter.

The “apocalypse” Baz and I discuss is the possible warming of the planet – which the XXXXXXXXX will partly motor – the increasingly inhospitableness of parts of Africa and southern Europe and the mass migration north of people in search of a habitable climate.

The drovers’ route might become a route for crowds of people seeking the temperate.

What rituals, what welcoming ceremonies, what performances of introduction could be devised to greet them?

What part in that could a place “to the side of”, “beside” the route play?

Now, where does the task of advocacy for “flood defences” fit in to this – what if we welcome the new flows of water, people, many-spotted ladybirds, forests of Himalayan Balsam along the rivers, Rhododendron stretching across Dartmoor, the spectre of agricultural communism. Not defences, but routes, flows.

Margaret Killjoy’s article in Dodgem Logic advocates establishing a communal permaculture as a response to the prospect of environmental change, deploying a very specific, communal, performative reflection – interweaving the use of voids and derelict sites as guerrilla allotments with an informal social agreement – but what if we build into that the necessity for developing forms and sites of ritual for the welcome and sustenance of those fleeing the heat? They will not be aggressive nomads. But they will transform the social relations of production in the English countryside – cheap labour in an authoritarian, segregated countryside? A return to manual labour? Socialised and common ownership? Pockets of anomaly?

Would the meadow-machine (as part of a larger complex of public and private property) be an effective ritual space for meetings of socially reparative, pre-apocalyptic groups, preparing their local permacultures within and in resistance to the narrative of catastrophe, to the side of, beside the route of migration, on a map of XXXXXXX?

We can begin the testing now – what happens if 39 people arrive to walk the meadow chart of XXXXXXXXXXXX? What would happen if they re-ran our Environment Agency task, but as an advocacy not of defences, but of integrated social, human, water, narrative, cultural and performance flows?