Over the summer, I retraced my steps across the network’s London walks. I started at Paddington, where there was a spill of rainwater that was caught in oil buckets. I took photos, and it struck me that if this were an installation it might be in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall.

I took the tube to Waterloo, and found the installation of beach huts on the South Bank. It was 4th August 2011, just before the riots. I went inside and listened to London’s beat. This moment of listening allowed the kind of attentiveness that Jean-Luc Nancy describes as ‘always on the edge of meaning’ (Nancy 2007: 7), a reflexivity that seeks relationality as my senses interweave, inviting ‘participation, sharing or contagion’ (Nancy 2007: 10). Out of habit I pushed my hair back from my face and watched a strand fall to the ground. I left it there, as I breathed the hut’s London. It felt surprising that I couldn’t smell the sea. With each breath, my body accumulates London’s toxicity, a mix of chemicals and metals I can neither see nor feel. I am part of its ecology, and it is part of mine. The materiality of London has agency and vitality, it adds to the ecosystem of my body – to the swarms of bacteria, microbiomes and parasites that make up what Jane Bennett calls the ‘array of bodies’ that are me (Bennett 2010: 122). I walked out of the hut, leaving the strand of hair, the dust of my skin and the exhaled carbon dioxide of my breath. I ingest the city, I was literally becoming London.

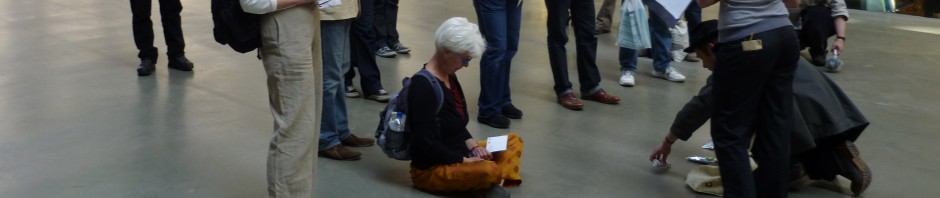

My walk in London was purposeful, although until I encountered the installation of beach huts, it was somewhat less playful than a Situationists’ derive. I was walking to learn how (or if) I remembered two performative walks I had undertaken as part of the AHRC network that had challenged me to reflect on environmental change through site-based performance. As the third in a trilogy of weekend events, London weekend was the accumulative effect of our time together and meant that network members had grown familiar with each other’s rhythms and patterns of thought, lending this weekend a particularly comfortable texture. Over the course of this weekend, we were led through the City of London and across the Thames to Tate Modern by Mel Evans and James Marriott, two membes of PLATFORM. Phil Smith, network member and a core member of Wrights and Sites, (mis)guided us around the area surrounding The Strand. As this blog has testifed, the two walks held contrasts of scale and rhythm: Mel and James took us to commercial sites associated with BP and in each setting they pieced together the narrative of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico with cool detachment, often refusing eye contact as they read the chilling details from a script. Phil, by contrast, engaged his audience intimately and conversationally, weaving together the history layered on the streets with more personal memories, artefacts and images. The PLATFORM walk maintained the detached anonymity of the City, and Mel and James’ refusal to domesticate its spaces amplified my sense of alienation to the spatial order of the architecture.

The images on the blog show the security Guards were largely impassive, scarcely registering our presence as we stared through windows that would easily encase most homes. The empty foyer of the University Superannuation Scheme building perhaps presented the most challenging moment in the walk, where we were reminded that we were implicated the environmental catastrophe of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill as we sat on sofas to hear how our pension plans depend on investment in BP. This global ecological crisis feels contagious, conceded in the toxic space of my own body, my embodied practices and written on my pay cheque. Theron Schmitt, writing about another PLATFORM walk, describes this feeling of complicity as ‘a profoundly doubled moment, overlapping representation and relation’ (Schmitt 2010: 292). My ecological consciousness was similarly raised by PLATFORM’s walk, and my reading of the cityscape in the refuge of the beach hut was haunted by its memory and, perhaps, tainted by my environmental double-standards.

But when the walk was over, I felt that I had left no trace, no mark or imprint on the City. I had ingested it, but this space of urban capitalism remained abstract, in Lefebvre’s terms, and it had resisted me (1991: 53).

Phil’s walk invited us to embody the city’s stories, to theatricalise its dead spaces and re-imagine the stories of the dead. When I retraced my steps three months later, I was not surprised that my body remembered the walk around the Strand. Standing in the garden in which Phil had told us Dickens had set the melodramatic demise of the fictional Lady Dedlock, I was haunted not only by the imaginary of ghosts of the ‘real’ dead people beneath my feet, but also the live people I missed from the first walk – and the comingling of both hauntings, to borrow Steve Pile’s words, allowed me to attend to the relational space we had produced by disrupting ‘notions of linear time and space’ (1996: 164).

When I returned, in the City I got lost. I could remember few details. Perhaps it was part of the political effectiveness of PLATFORM’s walk that I still felt shrunken by the vast scale of the buildings, and confused by their impassive indifference. Or perhaps I have a poor memory for facts. I found the USS building eventually with the aid of a map, and I looked through the window at the sofas, catching my reflection. The glimpse was fleeting, and in a moment I knew I would disappear again without leaving an impression. Precipitously, as this was just before the London riots, I understood why demonstrators and rioters sometimes want to smash windows. It’s one way to produce space.

I’ve pondered the ongoing argument around these two walks and I think that one key aspect is information-transfer – the Platform walk followed a particular version of the standard guided tour’s prioritising of information transfer, but (like the standard tour) did not allow much space for the tour group to test this information against their feelings, act in the moment on it, subject the tour itself to the same test as it was being asked to subject the companies to…

Phil makes an interesting point here… Although, without wanting to reignite the debate again, I’d simply note that my own experience of the Platform walk was that there was *plenty* of space between the set-piece narration sections for us to process our responses. Indeed we walked quite considerable distances between some of the stopping points. So I wonder if there’s also something here about the dynamics of group involvement in walks like this. The network group knew each other fairly well by that stage, and for the most part seemed deeply involved in private conversations during the walking bits of the Platform walk – did that in itself limit the ‘space’ for personal reflection? Whereas I tended to hang back from the group a bit becuase I was taking pictures for documentation purposes (and because I’m a sad loner). Conversely, with your walk Phil, there was much more of a conscious engagement with the group AS a group (and even an announced introduction of an outsider into the group, plus group role-play etc), so that the communal dimension was all part of it and hanging back as a sad loner would have felt inappropriate anyway? We were invited to reflect as a group, whereas I think the Platform walk was perhaps addressed more to individual reflection, in the sense Ranciere discusses in ‘The Emancipated Spectator’ (and as in their audio walk, obviously). But anyway, I think we may never agree on this! Thanks, Helen, for posting these thoughtful reflections…

the audience dynamic that Steve describes seems very important and I’m not sure I’ve picked up on that contrast before – there’s one other aspect I think we haven’t fully discussed and is directly relevant to the research here – the Platform walk was pretty focused in its thematic matter, while the Aldwych walk was very disparate – the Platform walk, while it gave us different invitations to experience the space tended to draw us back to the limited thematic – while the Aldwych walk was weak because it did not have some sort of spinal or matrix theme (like, say, the Devil’s Footprints does) – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MdEYlYJpkl0 – but it does have a crude mythogeography – a multiplicitous geography – which is the more likely to provoke a wish to defend, nurture, improve an environment?

this is worth a look:

http://blog.platformlondon.org/2011/11/28/platform-promenade-guest-blog-by-participant-hester-berry/