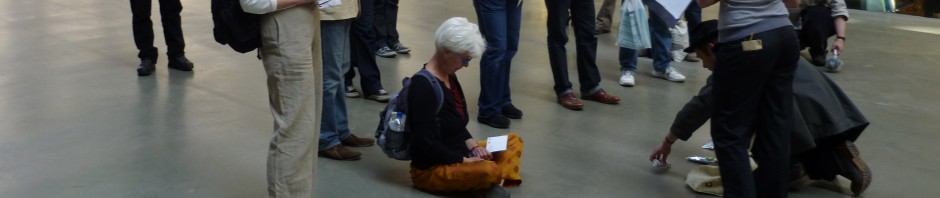

It’s oddly appropriate that, two weeks after posting a brief, “3 years on” blog piece remembering our Fountains Abbey network weekend, I found myself once again listening to John Fox, of Dead Good Guides, talking about his and Sue Gill’s collaborative life practice at their home on Morecambe Bay. The occasion, this last Friday 1st November 2013, was a one-day symposium at the Central School of Speech and Drama, New Perspectives on Ecological Performance Making, co-organised by PhD candidates Lisa Woynarski and Tanja Beer. They had succeeded admirably in bringing together a broad spectrum of people concerned with the connections between theatre/performance and environment/ecology, and the day was full of insights and provocations of various sorts. One of the nice things about it, on a personal level, was the sense of continuity it offered from our earlier network project — and indeed John remarked in his talk that he felt quite at home because pf the presence of so many of “the Fountains gang” – including our host at Central, Sally Mackey, and also Dee Heddon, Baz Kershaw, Wallace Heim and myself. At the same time, though, there seemed to me no cause for self-congratulation in terms of “establishing a new sub-discipline” or anything of that sort…

If anything, the number of different perspectives being presented demonstrated the lack of existing cohesion or agreement about what “ecological performance making” would even mean: for some, it’s about finding low-carbon solutions for traditional theatre practice (cue much discussion of LEDs as against tungsten bulbs), for some it’s about art as activism, for some its about using performance to cultivate a renewed attentiveness to the non-human environment, and so on… It’s a testament to Lisa and Tanja’s care and organisational skills that all these perspectives were brought together in one room for one day, so let’s hope the symposium prompts further productive discussion and collaboration.

At this moment in time, however, this gathering felt very marginal to the concerns of both theatre/performance studies at large, and indeed to the study of environment/ecology. In introducing the opening panel, as chair, Baz very generously described Wallace, Dee, Carl Lavery and myself as the “illumanati” of this emergent area of concern, but I felt strongly that the accolade was undeserved. Leaving aside the fact that it’s Baz himself, if anyone, who has earned it, there’s the more important point that we are not a secret society and we are certainly not the keepers of any special knowledge… Each one of us is simply scratching around the edges of something — Wallace from a primarily philosophical perspective, Dee as a walker and forest enthusiast, Carl as (it seems to me) a classical avant-gardist, and myself as someone with a vaguely Boy Scout-ish urge to do something useful by wandering up and down rivers. And all of this pales into infinitesimal insignificance, though, when one considers the wider challenges that Baz also alluded to in his opening remarks.

This is, he observed, both a hot and a cool moment. A hot moment because the planet is still warming and the urgency to do something radical about the situation – on a concerted, global scale – is more pressing than ever. And a cool moment because — after a few years of felt concern, around and about the COP15 summit of 2009? — the whole topic of climate change has “cooled off” in the media and the public consciousness. There seems to be more of a determination than ever to bury heads in the sand, to deny the scientific consensus — as evidenced recently by the press coverage of the latest IPCC report (UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), which spilled much ink over the report’s mention of a recent, unexpected slow-down in the rate of warming, but which merrily obscured the fact that climate scientists are more convinced than ever of the underlying trend — i.e. that human activity is driving potentially catastrophic changes in the climate.

For those of us working in higher education, these issues are given particular piquancy by a new report from Platform that points out the degree of collusion between British universities and the fossil fuel multinationals whose objective is to keep drilling for oil in ever-more-dangerous and sensitive environments. The report, Knowledge and Power, tells me for example that my own employer, the University of Manchester, last year took £64 million from BP in order to finance a new research centre — one explicitly directed to “help [BP’s] search for oil in deeper and more challenging environments.” This unholy alliance of BP and UoM, says the PR blurb, “enables BP to access the University’s world-class executive education, high-quality research facilities and its undergraduate talent pool” (quoted p.16). And yet at the same time, the University has the gall to be inviting staff to join “green impact teams” to ensure more sustainable energy use in its buildings… One suspects, in this context, that “green impact” translates merely as “cost saving”, given that the institution’s commitment to saving the planet is, to say the least, equivocal.

I am angry about this. Actually. Seriously fucking angry. And not least with myself for not bothering to research my employer’s dirty fingerprints before now. Question is, now what?

Of course, in the cultural sector, there have been very active campaigns running now for some time to get BP and Shell sponsorship out of the arts. The most prominent such activism in the last few years has been Liberate Tate‘s interventions (often in collaboration with Platform) at London’s Tate Galleries. But if I needed further evidence of the “cooling climate” for such protest, it was provided by a visit — the day after the Central symposium — to Tate Britain. My intention was to once again tour the gallery with my iPod listening to Tate a Tate, the site-specific audio work created by Platform, Liberate Tate and Art Not Oil…

This work had quite an impact on me when I first experienced it in the spring of 2012, shortly after the tours were released online… The aesthetic dimensions of it intrigued me – a guerrilla audio guide providing alterative readings of the works in Tate Britain and Tate Modern, and linked by a musical protest song mash-up for listening to on the Tate Boat that links them. (In fact, I realised this year that I subconsciously lifted this walk-boat-walk structure for the Multi-Story Water performances we made in Shipley…) Admittedly I wasn’t that taken with the Tate Modern tour, which seemed to me to have little intrinsically to do with the building or its displays: instead, it simply directed you at certain pictures and then used various lateral connections to launch into diatribes which — though informative — lacked the conceptual or sensory allure of the best contemporary art, and thus somehow “fell short” of the site it had specified for itself. But the Tate Britain tour was, for me, far more compelling… more layered in its audio textures, more striking in its ideas.

This work had quite an impact on me when I first experienced it in the spring of 2012, shortly after the tours were released online… The aesthetic dimensions of it intrigued me – a guerrilla audio guide providing alterative readings of the works in Tate Britain and Tate Modern, and linked by a musical protest song mash-up for listening to on the Tate Boat that links them. (In fact, I realised this year that I subconsciously lifted this walk-boat-walk structure for the Multi-Story Water performances we made in Shipley…) Admittedly I wasn’t that taken with the Tate Modern tour, which seemed to me to have little intrinsically to do with the building or its displays: instead, it simply directed you at certain pictures and then used various lateral connections to launch into diatribes which — though informative — lacked the conceptual or sensory allure of the best contemporary art, and thus somehow “fell short” of the site it had specified for itself. But the Tate Britain tour was, for me, far more compelling… more layered in its audio textures, more striking in its ideas.

Beginning in the front foyer of the building, and then guiding the listener to lock him or herself into a basement toilet cubicle, the tour begins with a history of the site itself — as what was once swampy, riverside marshland. Drained in the late 18th Century, it provided the site for Millbank Penitentiary — England’s first, large-scale modern prison, and still the only one to be built explicitly along the guidelines mapped out by Jeremy Bentham in his writings on the Panopticon (latterly beloved of Foucauldians the world over). Taking this fascinating titbit as its conceptual hinge, the soundwork then proposes that the listener is in the centre of a new “Panaudicon”. By locking down one’s spatial co-ordinates, one can extend one’s hearing range for thousands of miles in different directions from this central point. Guided to the Clore Gallery, housing the Tate’s unmatchable collection of Turner paintings, one is invited to sit down in front of this canvas…

… and to listen carefully as sounds come directly through it, magnified by the Panaudicon from their spatial source across the globe and, indeed, back in time. Thus, looking at the mysterious, single-tree landscape of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, we hear the haunting sounds of whales being hunted near to extinction for the oil their bodies contain. This brutal trade finally ended, we are informed, not because of any conservationist concern for the species, but simply because it became uneconomic. A new, more profitable source of oil had been identified… Turning through 90 degrees on the gallery bench, we are invited to look through this painting, towards a different point on the globe, the Caspian Sea…

Looking at — and listening through — this particularly smug-looking portrait of a wealthy 18th Century gentleman, reclining in a forested glade, we hear of the first, filthy, dangerous attempts to drill for fossil fuel oil. The juxtaposition of sound and image, at this moment on the tour in particular, haunted me for months after first experiencing it. But returning to Tate Britain this weekend, I discovered that the experience was unrecoverable. I had been expecting some changes to the “hang” in the gallery, and that the tour might therefore be tricky to negotiate some 18 months on from its inception. What I had not expected was to discover that the entire recording was redundant. Leaving aside the installation work going on in the central rotunda (which was masked off, making the various audio instructions to move through it difficult to negotiate…), there was the stark fact that every single painting referenced by the guide was not only absent from its anticipated spot… it was nowhere to be seen in the gallery at all. I hunted high and low for Childe Harold and Sir Brooke Boothby — all to no avail.

The audio guide concludes with a tour de force encounter with this painting, Holman Hunt’s The Awakening Conscience. Here, the sound effects of a glorious, birdsong-filled garden outside the window (the window into which the painting’s viewer is ostensibly peering) brought the canvas’s colours to life with an eerie, supra-natural vividness when I first encountered it. Something phenomenological happened for me, that I can’t quite articulate, even as the voice-over adopted the classic tone of an art critic — offering a disquisition on the content of the image, while also inviting metaphorial reflection on the theme of conscience… Just as the woman, stunned by the natural beauty of the garden outside, arises from the lap of the leering gentleman — apparently resisting the temptation to sin — so art (proposes the recording) needs to be the conscience of society, not merely a whore to corporate interests. (OK, the gender politics here are a little fuzzy, but leaving that aside…) As the narration concludes, the birdsong continues for a sustained period, so that you are left uncertain when to pull away from the painting (“is it over now?”), held by the stare of the protagonist and the light in the garden…

Again, though, none of this was repeatable this weekend. The painting was not in its designated spot — nor indeed anywhere to be seen. Now, of course, this might all be perfectly innocent. The Tate’s permanent collection is enormous, far too extensive to all be on dislay at any given moment, and they do have a policy to periodically alter what is hung and what is stored away. But just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not after you, and there was something about the fact that the audio tour’s potential effects had been so systematically destroyed — every painting referenced being so mysteriously absent — that persuaded me that something quite deliberate had occurred here. Tate has been well aware of Liberate Tate’s activities, after all (they’ve been discussed at board meetings) … and it wouldn’t have been hard for the gallery’s curators to listen to the recording and take the necessary action to destroy any potential impact it had as an artwork. The audio tour’s ambition to be a “permanent installation” has proved sadly temporary. The gallery’s conscience, rather than being awakened, has been decisely smothered.

More than that, though… For those of us who see conspiracies everywhere, it’s difficult to avoid the fact that, directly adjacent to the room that once housed Childe Harold and Sir Brooke Boothby, there’s currently an exhibition of Constable paintings titled “Nature and Nostalgia”. An exhibition prominently sponsored — you guessed it — by BP (a corporation who can afford to be nostalgic about nature, since they clearly don’t care much about its present or future). On this half-term weekend, moreover, BP’s interest in time has been manifested thus…

The Time Loop allows families to tour the gallery as if on a Doctor-Who-ish time travel journey, making unexpected connections between different periods…. (just as the audio tour had…?). As a consequence, the BP name and logo are dotted all over the building, linking different exhibits. It is difficult to imagine Tate having been quite so unashamedly celebratory of its links with the oil giant last year, or the year before… Deepwater Horizon, it would seeem, has faded from the public memory like a bad smell, wafted away by artistic air freshener.

The Time Loop allows families to tour the gallery as if on a Doctor-Who-ish time travel journey, making unexpected connections between different periods…. (just as the audio tour had…?). As a consequence, the BP name and logo are dotted all over the building, linking different exhibits. It is difficult to imagine Tate having been quite so unashamedly celebratory of its links with the oil giant last year, or the year before… Deepwater Horizon, it would seeem, has faded from the public memory like a bad smell, wafted away by artistic air freshener.

And meanwhile, in Tate Britain’s temporary exhibition galleries, the current major exhibition is this:

I asked a docent what the exhibition was about. She told me that it was about the way that art has been vandalised over the centuries… but how sometimes the fact of the art having been vandalised makes it more memorable and more important.

I asked a docent what the exhibition was about. She told me that it was about the way that art has been vandalised over the centuries… but how sometimes the fact of the art having been vandalised makes it more memorable and more important.

There’s an irony here that I can’t quite put my finger on.

+++++++++

November 26th update to the above:

Unsurprisingly, Liberate Tate themselves have clearly had their eye on the developments within Tate Modern, re-BP’s sponsorship of the newly unveiled exhibits… They entered the gallery with characteristic brassiness very shortly after the re-opening, to perform Parts Per Million, a simple but rather brilliant intervention – which is also sobering and scary in its implications. See Youtube link below: